Food insecurity is a reality for many South African households, with approximately 50% of households living under the poverty line and not being able to afford basic healthy eating. Low-income households typically spend about a third of total expenditure on food.

The spread of the global COVID-19 pandemic to South Africa is causing further pressure on vulnerable households facing temporary or permanent employment interruptions. In addition, the primary caretakers of these households now have more mouths to feed, including children that previously benefited from the National School Feeding Programme also relying on their primary care givers for food.

The COVID-19 outbreak in South Africa has forced government to develop interventions to ensure vulnerable households have access to safe and nutritious food during the current state of emergency. One being implemented on a provincial government level involves the distribution of food aid parcels to vulnerable households. The food parcels will see may households through one of the greatest pandemics of our time.

But are these food parcels nutritionally adequate?

Food parcels

Gauteng is home to just over a quarter of the South Africa population and is viewed as the economic hub of the country. In Gauteng the food parcel relief scheme is available to citizens who earn a combined household income of less than R3,600, as well as to recipients of South African social security agency pensioner, disability, child welfare and military veteran grants.

Read more:

Social protection responses to the COVID-19 lockdown in South Africa

Each food aid parcel being distributed in Gauteng includes: starch-rich foods (10kg maize meal and 5kg rice), protein-source foods (1kg soya, two tins of baked beans, two tins of fish and 880g peanut butter), two litres of cooking oil, one packet of tea bags, 2.5kg sugar, 1kg salt and three non-food items (one bottle of dish-washing liquid, one bottle of all-purpose cleaner and two bars of laundry washing soap). In the Gauteng province approximately 7,000 food parcels are requested daily. By early April 8,000 families had received food parcels.

The president, Cyril Ramaphosa, has also announced that a further 250,000 parcels will be distributed across the country. The implementation of technology-based solutions to provide food assistance at scale through vouchers and cash transfers will also be incorporated to ensure that help reaches those who need it faster and more efficiently.

Our objective was to determine whether the nutritional value of this food parcel met the requirements of what is generally accepted as a nutritionally balanced diet. In this case a balanced diet was defined based on the nationally accepted nutritional guidelines: the South African food based dietary guidelines combined with the eating patterns suggested in the guidelines for healthy eating.

Benchmark values of selected nutrients were obtained from the World Health Organisation. In this case a reference family was assumed to consist of one adult female, one adult male (older than 16 years), an older child (aged 10 to 14 years) and a younger child (aged 3 to 9 years).

The Gauteng food aid parcel has a retail value to the recipient household of approximately R507 (based on current online retail prices) with a total weight of approximately 30kg.

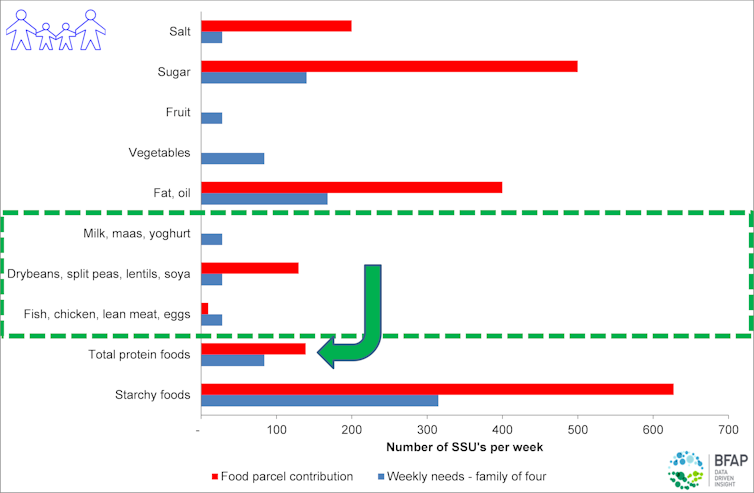

From a food group perspective the Gauteng weekly food parcel relies heavily on starch-rich staple foods (maize meal and rice) and could potentially provide the reference family of four people with enough staple food servings for a two week period. The food parcel could furthermore provide the reference family with enough protein-source foods and oil for approximately 1.5 weeks and 2 weeks respectively. But the food parcel is lacking in dietary diversity in relation to items such as dairy, eggs, fruits and vegetables.

Macro-nutrients are the energy providing substances consumed in the form of carbohydrates, fats and proteins. Considering macro-nutrients, we found that the food parcels had more than adequate carbohydrate, protein and fat content compared with nutritional guidelines.

Dairy, eggs, fruits and vegetables supply the much needed recommended dietary amounts of zinc, iron and vitamin A which are critical micro-nutrients of concern in South African diets. These three micro-nutrients are essential for an optimally functional immune system and immune cell growth which is crucial in assisting the body in fighting diseases including optimistic infections such as COVID-19.

Iron has an important role to play in cellular processes assisting the body in fighting off pathogens by increasing the number of free radicals that can destroy them. Vitamin A provides cell structure to the respiratory tract and zinc maintains the integrity of the mucous membrane. Both are essential in fighting off respiratory infections. The food parcel provides a sufficient amount of zinc and iron but vitamin A isn’t up to the recommended level.

In addition, the lack of fresh produce causes a shocking 98% deficit in daily recommended allowance for vitamin C. Vitamin C protects cells from oxidative stress which reduces the occurrence of free radicals that can cause inflammation. Adequate vitamin C ensures that the immune system is able to fight off disease.

Our analysis also suggests that there could be a reduction in the salt and sugar content of the food parcels. The country has legislation aimed at reducing the intake of both.

What needs to be done

Based on our analysis we would recommend the following changes to the food aid parcels:

- Staple foods: reduce the quantity of maize meal and consider the inclusion of preferably self-raising wheat flour (eliminating the need to include baking powder or yeast).

- Animal source foods: include eggs and shelf stable milk.

- Legumes: include dried beans or samp and beans.

- Vegetables: include shelf stable tomatoes and vegetables.

- Fruit: include oranges and apples, which are currently in season.

- Flavouring: Reduce the quantity of sugar and salt and add soup powder or stock.

Providing food to the most vulnerable during the pandemic will ensure relief where it is most needed. Striving to provide more nutritional food can ensure better health outcomes that will reach beyond the pandemic.![]()

Authors:

Hester Vermeulen, Senior analyst, Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy (BFAP), University of Pretoria; Carmen Muller, Researcher and PhD student in Human Nutrition, University of Pretoria, and Hettie Carina Schönfeldt, Professor and Director ARUA CoE Food Security, University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

related Articles

‘If we fail on food, we fail on everything’

“If there’s one thing I take away, [it’s that] ‘if we fail on food, we fail on everything’,” says CoE-FS…

New book: “Resilience and Food Security in a Food Systems Context”

Resilience and Food Security in a Food Systems Context is a recently published, open-access resource which delves into why we…

A personal reflection on the ‘2023 Lancet Series on Breastfeeding’

Dr Nazeeia Sayed and her daughter on a work trip. Photo Supplied. By Dr Nazeeia Sayed, Researcher, School of Public…