Fruit vendor in Church street, Johannesburg, South Africa. Photo: Ossewa/Wikimedia Commons.

When Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) released the consumer price index (CPI) data for February 2023, the high food prices caused justifiable concern. The overall annual inflation rate, based on all items in the CPI, was 7%; food inflation, based only on the food items in the CPI, was twice that level at 14%. So, what does this mean?

Well, the difference between the overall CPI and food inflation matters immensely because many wage negotiations and other adjustments to incomes, such as for government grants, are linked to the overall CPI. The state pension, for example, is being increased by just 5.03% this year, leaving millions of pensioners unable to buy the same amount of food as they could a year ago. Poorer families also spend a far higher proportion of their incomes on food, so are far more negatively affected than wealthier families when food inflation is high. Therefore, the large gap between food and overall inflation drives greater inequality and poverty. And in a country where at least half the population are already unable to afford a healthy diet, it leaves even more people hungry.

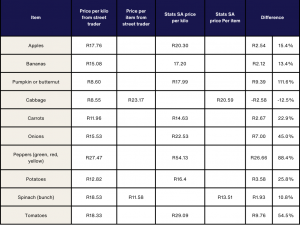

With food prices increasing rapidly, it becomes essential to look at how food can be kept affordable. In 2022, the DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security’s (CoE‑FS) “Urban Food System” project began tracking the prices of 10 fruits and vegetables — fresh produce that is essential for healthy and balanced diets — sold by street traders (Table 1).

- Apples sold in Johannesburg. Photo: Sylvia Pilane.

- Nomfundo Mngika’s collection. Photo: Nomfundo Mngika.

- Sylvia’s collection. Photo: Sylvia Pilane.

- Peppers bought from a local street trader. Photo: Emihle Mandita.

- Spinach bought in Ivory Park. Photo: Dikeledi Phasha.

- Fresh produce at a local street trader. Photo: Nomfundo Mngika.

In addition to the prevailing circumstances, i.e., price inflation and the impact on our most vulnerable, the need to start price-tracking became apparent, following prior research with food street traders had revealed that they appeared to be selling at cheaper prices than the supermarkets. We also realised that there was no data available on informal sector prices, as the Stats SA CPI figures are based on prices at formal retail outlets.

Street trader savings

In response, we now have six data collectors from three different areas purchase the 10 identified fruit and vegetables on a bimonthly basis. All items are weighed to give per-kilo prices, and the data is compiled to calculate average prices.

Across the 10 items, nine of them are being sold more cheaply by street traders than by the formal sector (Table 1). The potential savings per kilo, when buying from street traders, range from R2.12 on bananas, to R26.66 on peppers. Only the pricing per cabbage comes in cheaper in the formal sector than from the street traders, although these figures are not necessarily comparable as Stats SA does not provide any per-kilo prices for cabbages. Comparing cabbages and spinach by the price per item is nonideal, as cabbages and bunches of spinach vary greatly in size and weight. For example, the cabbages that our data collectors bought during February 2023 ranged from 1.63 kg up to 4.75 kg.

Markups still made

Examining items more closely starts to reveal where money is going. For example, onions were selling for R22.53 per kilo in February 2023, an increase of 47.25% from the R15.30 per kilo in February 2022. The national average wholesale price of onions sold at municipal fresh produce markets in February 2023 was R6.16 per kilo of which R5.39 goes to the farmer, who still must pay for transport to the market and all production costs.

Almost all the produce that our data collectors purchased from street traders is sourced at these municipal markets, as is much of the fresh produce sold by formal retailers. The markup from the wholesale market price to the retail price of onions averaged R16.37 per kilo — over 265%. Street traders selling at R15.53 per kilo were saving the customer R7.00 per kilo, but still making money with a healthy markup.

Table 1: Comparing prices from street traders and formal sector, February 2023 (Sources: Stats SA CPI Average Prices Feb-13, and CoE-FS Urban Food System Project price tracking Feb-23)

Quality and accessibility

Many people I talk to about purchasing fresh produce from street traders immediately ask about the quality. Our data collectors live in the low-income neighbourhoods from which they purchase produce for themselves and their families. They balance factors of price and quality in their buying decisions, and are not seeking or sending us data simply to find the cheapest produce available.

In addition to sending price information, they also make notes about quality and, overwhelmingly, report that items were fresh and of a good standard. They also send pictures of the items purchased, which show produce that appears to be good quality.

A trolley trader in Ivory Park. Photo: Dikeledi Phasha.

Other factors, beyond price, that make the fruit and vegetables from street traders accessible include that they are sold very close to where people live, or close to where they go to work, thus, there are no additional transport costs.

Furthermore, the street traders from whom our data collectors purchase include women selling on the corner of their streets, just a few minutes’ walk away, and trolley traders who come to their homes. The data collectors are also buying in small quantities, which makes food accessible for those on low and unreliable incomes, and for those without refrigeration, or reliable refrigeration, which is more of an issue with loadshedding. The apples and bananas are often sold loose, between R2.00 and R4.00 each. A typical purchase is a small packet or plate of tomatoes or onions, or a half or quarter cabbage, being sold for R5.00 or R10.00.

Traders’ contribution

We are eight months into the price-tracking, and once we have a full year of data, we will conduct further analysis and publish the full findings.

But, with rising food costs, and the consequences thereof, we want to show what we are seeing, and we look forward to sharing more information in the future.

It seems clear that street traders are performing a vital service by making fruit and vegetables more accessible, and expanded and improved support for the street trading sector can make an even greater contribution to reducing levels of hunger.

Dr Marc Wegerif

Senior lecturer and researcher at the University of Pretoria, and lead on the ‘Urban Food System’ project of the DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security (CoE-FS).

related Articles

South African cities face hunger and food insecurity as cost of living...

Originally published by the Mail&Guardian. “South Africa’s major cities are home to millions of people facing hunger and food insecurity…

CoE-FS 10th Anniversary Symposium – Governance and policy

Date: Wednesday, 22 May 2024 Time: 10h00 – 12h00 (SAST) Register for Zoom here. Co-chaired by Professor Julian May (CoE-FS…

Meet the grantee: Thato Mokgalagadi

Thato Mokgalagadi, a student currently doing her MSocSci Development Studies degree at CoE-FS co-host institution, the University of Pretoria. Photo:…