This month marks a special milestone for our fellow Oscar Sithole, who has published his first peer-reviewed journal article in the Discover journal co-authored by Oscar’s supervisor and CoE-FS PI Dr Marc Wegerif. This paper, a reflection of Oscar’s impressive Master’s research is a moment worth celebrating – not only for Oscar’s academic journey, but also for the communities his work centres. This collaborative research shines a light on the cart traders who move through township streets each day, calling out their produce and bringing fresh food directly to people’s doorsteps. Their work exposes a vibrant, overlooked part of South Africa’s food system often undervalued partly because it is framed as “informal.”

Reframing the Food System from Below

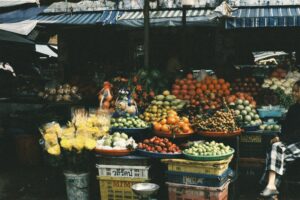

Public debates on food security typically focus on supermarkets, corporate value chains and formal retail. Yet for millions of low-income households, especially in townships, fresh food is accessed not through corporate channels but through street-based traders pushing carts from yard to yard. These traders are central to everyday nutrition, affordability, and access but are rarely acknowledged as such.

For Marc, the term informal obscures the real logic and effectiveness of these systems.

Marc, Oscar and a fellow PhD student at Science Forum 2025

“If we’re interested in people in poverty, we have to be interested in what they organise for themselves,” he explains. “These aren’t NGO projects or government programmes. They’re long-standing systems people have created that work.”

Marc and Oscar’s combined research reframes this system not as an improvised survival strategy, but as a structured, socially embedded, non-corporate food economy that plays a crucial role in urban food security.

From Curiosity to Inquiry

Oscar’s interest began on the streets of Soshanguve, where he moved from rural Mpumalanga to study.

“I grew up where households had home gardens,” he explains. “Seeing men pushing carts and selling fresh produce at people’s gates was completely new to me. I wanted to understand why this model existed and how it worked.”

That curiosity grew into formal research. Over several months, Oscar systematically compared the prices of key fresh-produce items sold by cart traders with those at the nearest supermarket. The results were decisive: cart traders consistently sold produce at significantly lower prices, sometimes around half the price per kilogram.

“Shoprite is branded as the affordable option,” Oscar notes, “but for many households in Soshanguve, the cheaper and more accessible choice is the trader who comes to their door.”

This finding illustrates why Oscar and Marc argue

Car traders in Shoshanguve by Oscar Sithole

that serious food-systems research must begin with those navigating poverty — the subaltern — and the systems they build to secure food.

Why the language of “Informality” falls short

In policy and research, traders like these are often grouped under labels such as “informal traders,” “hawkers,” or “vendors.” Marc and Oscar challenge this language.

First, calling them informal implies that they operate outside the formal economy. In reality, they source their produce from municipal fresh-produce markets, regulated, publicly owned spaces that are integral to the national food system.

Second, language determines value. Marc explains:

“If the organisations representing these workers call themselves traders, then respectfully, so should we. ‘Trader’ recognises their economic role. ‘Vendor’ or ‘hawker’ can diminish it.”

Oscar adds that while terminology matters, recognition must go further: planning and regulation must differentiate mobile traders from stationary street traders and create conditions for them to operate safely and effectively. Naming them as traders within a people-driven food system shifts the narrative.

Debunking the myths and revealing a safe, accessible food system

Dr Sithole is dedicated to food system myth-busting.

Phot by EyeScape

A central finding of Oscar’s research is the degree to which cart traders are embedded in their communities. They primarily serve households living below the poverty line, many reliant on social grants. Elderly people, people with disabilities and those with limited mobility rely

heavily on the convenience of doorstep delivery, especially where transport costs are prohibitive.

Because traders and customers know one another, interest-free credit is often offered informally: customers take produce today and pay on grant day. Food nearing the end of its shelf life is often given away to families in need, reducing waste while strengthening social solidarity.

This relational embeddedness shapes perceptions of food quality and safety. Customers negotiate, choose, and hold traders accountable:

“People simply stop buying from traders who sell poor quality produce,” Oscar explains. “There’s direct accountability built into the relationship.”

This community-based system ensures affordability, flexibility and trust, elements often missing from formal retail.

Municipal Markets: The Public Backbone Supporting Cart Traders

Another key insight from Marc and Oscar’s work is the role of municipal fresh-produce markets, such as the Tshwane Market and Johannesburg Market. These are public assets that form the backbone of the fresh-produce economy.

Farmers deliver produce to the market; traders purchase it and distribute it through townships and cities. Through discussions with market agents and managers, Marc estimates that 50–70% of all sales from these markets go to micro-enterprises and street traders.

That means billions of rand in produce each year flows through non-corporate channels, a scale far larger than commonly acknowledged.

“When you zoom out from one cart trader to the level of the market system, you realise this is a substantial sector,” Marc says. “It is central to how urban South Africans access fresh fruit and vegetables.”

The perishability of crops like spinach has also created a dynamic relationship between small-scale farmers, “bakkie traders,” and cart traders, reinforcing a flexible, resilient supply chain. Taken together, these relationships form a relational food economy that reaches communities supermarkets struggle — or choose not to serve. Read more on municipal market’s in Dr Wegerif’s recent Conversation article.

Municpal Markets as a backbone of the food system.

PHoto by Pexelsnot — to serve.

Implications for Policy and Planning

Marc and Oscar’s research offers several clear implications for developing more inclusive urban food systems:

1. Recognise cart traders as core food-system actors

They must be included in urban food-system planning, not relegated to by-law enforcement.

2. Design by-laws and regulations for mobile traders

Current frameworks primarily target stationary traders, leaving mobile traders unaccounted for.

3. Invest in supportive infrastructure

Safe pavements, functioning roads and accessible public markets directly improve traders’ operations and community access to food.

4. Protect and strengthen municipal markets

As public institutions, these markets are vital to small-scale producers and traders. They must be safeguarded from privatisation or neglect.

5. Rethink how we measure food access

For many households, access is about proximity, mobility, trust and the ability to negotiate credit — not just supermarket pricing.

Not marginal – rather Indispensable.

By tracing the everyday movements of cart traders and the public institutions that support them, Oscar and Marc reveal a system that has long been hidden in plain sight. Their work reframes these traders not as marginal actors at the fringes of the economy but as central contributors to food affordability, accessibility and dignity.

As Marc puts it:

“If people in difficult circumstances organise something themselves and it lasts, there is a logic there that we need to understand.”

This emergent research contributes to a broader shift: from seeing these traders as an “informal problem” to acknowledging them as an indispensable part of South Africa’s food system from below.