South Africa has had the biggest listeriosis outbreak in the world that resulted in more than 180 deathsto date. The Conversation Africa’s health editor Candice Bailey spoke to Prof Lise Korsten about the challenges around food safety in the country.

What’s challenging about the pathogen that causes listeriosis?

The pathogen – listeria monocytogenes – causes the deadly disease in nature and uses food as a vehicle to invade the human body. Once it enters the body it “switches gears” and becomes lethal, causing symptoms such as nausea and diarrhoea – and even death.

As with many other food-borne pathogens, listeria can coexist with other microorganisms in water and soil ecosystems or on plants. The bacteria can survive even under stressful conditions, such as refrigeration. It can proliferate even when other microorganisms die off. And it even competes with other microorganisms for nutrients and space.

What does the outbreak tell us about food safety in South Africa?

South Africa was ill prepared for this devastating food safety outbreak. It is perhaps a reflection of the weaknesses in the whole food system.

There are several problems. Pieces of legislation that manage how food safety is handled remain outdated. It means that the systems in place are inadequate. This includes detecting and verifying potential problems.

On top of this there is a critical shortage of regulators, inspectors, laboratory personal, scientists and auditors.

These shortcomings were all evident in the extensive delay between the first reported case in January 2017, the announcement of the outbreak in December 2017 and the source being identified in March 2018. In the intervening 14 months, more than 180 people died and close to a thousand were affected.

In addition to outdated legislation South Africa has been dealing with a lack of effective regulation in the food sector. Industry has relied on self regulation in the absence of an effective regulatory system. Product recall is also not common despite being a requirement in food safety systems.

Due to the gaps in the system companies can become complacent and provide sub-standard products if not pressured to effectively self regulate.

A food safety outbreak was imminent and the scientific community was aware that it could happen – but not on this scale.

What does this mean from a food safety perspective?

Listeria is a potential hazard in food production, processing and food handling environments all over the world.

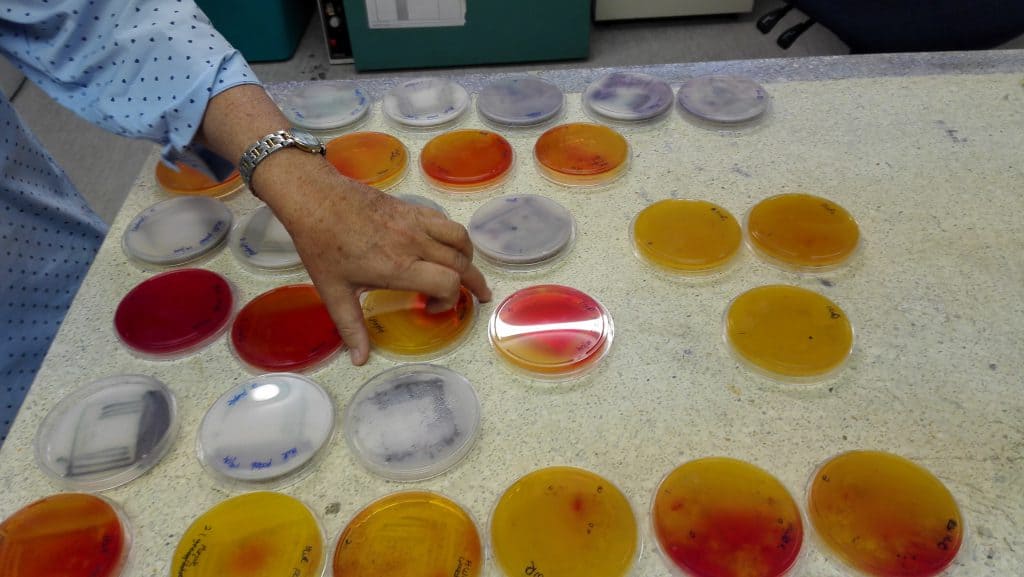

The pathogen can be difficult to trace and kill, particularly if effective cleaning schedules are not followed. Once the bacteria is introduced, it is able to hide in difficult to clean places and often survives in microbial biofilms (slimy layers), where it is protected against harsh cleaning agents. It prefers to breed in wet areas, particularly near drains which are difficult to effectively manage.

Once introduced into a processing plant, listeria is difficult to remove and can easily spread through a factory. Effective monitoring is as important as good cleaning programmes.

The emphasis should be on continually improving food safety management systems. But companies can be tempted to take short cuts as they balance between consistently delivering affordable, nutritious and safe food and turning a profit.

How do we solve the problem?

The South African government should consider establishing a national food safety authority. The idea has been proposed with suggestions of different governing models over the past 10 years. But none of these have gained traction.

The fact that there is no central authority or coordinated framework is problematic as it means there is no coordinated central point or one stop shop that deals with all import, export and local food control to protect consumers.

A central authority would shorten the time frame between the initial outbreak, identifying the source and product recall. It could also control imports and prevent illegal dumping and movements of counterfeit goods more effectively.

It would mean that technical experts in food science, food microbiology, plant pathology and animal science etc. could be used more effectively to benefit a national food safety framework.

At the moment most commercial South African companies involved in food production and processing particularly those who export, have to go through expensive certification. This is a self-regulatory system that relies on good auditors and accredited certification bodies. The challenge is that the country has a serious shortage of competent auditors/inspectors and local certification bodies.

Another problem is that when there are threats of a foodborne disease, the government, industry and academia work in silos and don’t share knowledge or technologies that could benefit the whole country.

In addition to a centralised food safety authority, there have also been suggestions that the agricultural and food legislative framework should be revised and the fragmented and outdated regulations be amended or new legislation promulgated.

Lastly, certification bodies responsible for certifying food safety management systems and test laboratories must reassess their role in supporting an effective food safety system.

Lise Korsten is Professor in the Department of Microbiology and Plant Pathology, University of Pretoria and the co-director of the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

related Articles

Three CoE-FS nominations for this year’s ‘Science Oscars of South Africa’

Some of the CoE-FS’s staff, researchers and Steering Committee. Photo Ross Jansen/CoE-FS. The DSTI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security…

CoE-FS co-director Lise Korsten awarded prestigious hon doc from Ghent University

Five tips to better food safety in the kitchen

Here are five tips to better food safety in the kitchen: Always wash counters, knives and containers. Photo Kaboompics.com/Pexels. 2….