In commemoration of World Food Day, Professor Julian May, director of the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security (CoE-FS) at the University of the Western Cape (UWC), shares insights on understanding the nature of the problem of food security, and how it could be addressed in South Africa. Listen to summary podcast below.

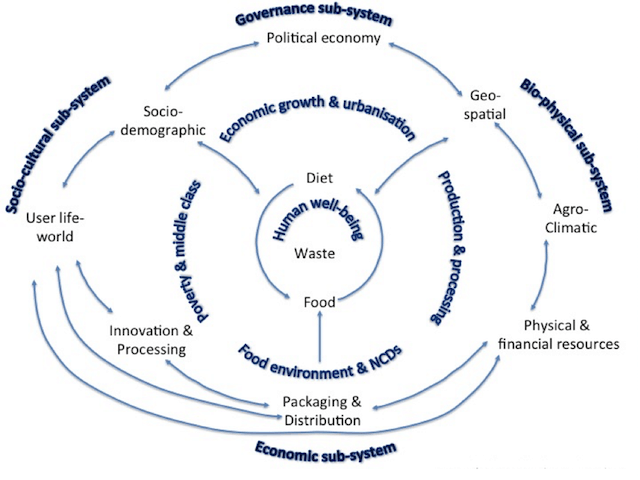

Image by Julian May in Food Security Working Paper #002. Adapted from: Sobal et al (1998); Ostrom (2009)

Food security and nutrition are receiving renewed attention in international and national policy agendas. This has been accompanied by a profusion of concepts borrowed from diverse disciplines and then employed to describe challenges to achieving food security and adequate nutrition. The Committee on World Food Security (CFS) defines food security as existing “…when all people at all times have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.”

The CoE-FS has adopted this definition, but recognises that there are important capabilities that go beyond the availability of food that is nourishing, the resources with which to access this food and the manner in which food is utilised. These include the stability of the food system in terms of prices, quality and safety, the agency of those in the food system, including consumers, to make informed choices, and even the physical ability to absorb the nutrients that are provided by food.

Through the Centre’s collaborative approach to research we’ve established that food security – particularly in South Africa – is something that results from a complex system of production, of processing, of distribution, and ultimately of the utilisation of food and the management of the waste that is caused from all of these activities.

That complexity leads to many puzzles. For instance, we know that the number of people who report to have experienced hunger have been halved since the 1990s, according to the Poverty Trends in South Africa survey by Statistics South Africa. In the case of the group most vulnerable to effects of food insecurity, South Africa’s children, the percentage of children reported as going hungry has fallen from 41 per cent in 1994 to 13 per cent in 2015. So we’re doing quite well in that regard. But at the same time, the 2017 South African Early Childhood Review reports that thirty per cent of young children fall below the food poverty line. As a result, we find that stunting in children – children below the height that they ought to be for their age – has not come down, and may even have gone up.

The recent Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) indicate that about 27% of South African children are stunted – which is staggeringly high and makes us an outlier even among countries of similar wealth. Child stunting is an indicator of long-term malnutrition, and directly affects the physical and cognitive ability of children. This has negative consequences for their educational achievements and health, and ultimately upon how well these children will do when they enter the labour market. The DHS goes further to show that only 23% of children age 6-23 months meet the criteria for a minimum acceptable diet.

We need to understand why this persists when we provide child grants, we fortify food, we provide free primary health care and we provide free vitamin supplementation. As an example, the Early Childhood Review reports that vitamin A supplementation coverage rates have improved and in 2015, over 57 per cent of children aged 12-59 months received a vitamin A dose at a public facility. Nonethess, over 40 per cent of young children still suffer from vitamin A deficiency. It seems that we have the right policies, but yet something is still not working.

If we are to find places to intervene to improve people’s access to food, and to improve the quality of the food that they’re eating – and quality in terms of both its safety as well as its nutritional value – we will have to identify the appropriate leverage points, the most useful pressure points where policymakers can do something about food security.

That, is quite different from thinking about other kinds of deprivation that people experience – such as unemployment or access to services as examples. Almost two-thirds of children under 6 in South Africa live in the poorest 40% of households. Almost half of these households have no link to the labour market at all, while Statistics SA’s General Household Survey shows that 45 per cent of all children live in rural areas, mostly in traditional housing, 9 per cent live in informal settlements or backyard shacks, and over 30 per cent live in households that do not have adequate water on site or adequate sanitation.

In the case of food security, there often are unintended consequences of different kinds of policy. And we have to accept and appreciate that it is not always within the ability or the powers of the government to do something about the things that cause food security. It’s a problem that involves not only government. It involves the private sector; it involves decisions that individual people and families take in their homes; and it involves decisions that people take when they are buying food.

We should also recognise that nutrition is a critical component of food security. There are several reasons for this.

The first is the nutrition of very young children. We know that if children don’t receive enough energy, and if they do not receive the right kinds of nutrients, it has a long-lasting impact on their future. Children who may be eating enough, but who are not eating well enough experience other forms of malnutrition. The Early Childhood Development Review reports that, 13 per cent of children under the age of 5 years are overweight. These children are likely to become overwieght or obese adolescents and adults, and the DHS reports that the prevalence of both has increased since 1998, and that in 2016, 68 per cent of South African women and 31 per cent of men were overweight or obese.

Proper nutrition is thus also important for adults. In South Africa and increasingly across Africa, we are experiencing – amid concerns of food security – problems of overconsumption where people are consuming too much energy. And not necessarily nutritious food, but food that causes people to become overweight and obese.

This leads to several problems, not only at the individual level, but also at the societal and public health level. The first is the probably of increased risk of non-communicable diseases, such as hypertension and Type 2 diabetes and some cancers such endometrial, breast and colon. The second are the difficulties that come with being overweight such as musculoskeletal risks including osteoarthritis and mobility problems. People wind up being less healthy than they could have been had they had diets that were nutritious rather than obesogenic.

Increasingly, food security is now recognised as being a ‘wicked problem’; in this case, wickedness means that it’s a problem that is difficult to solve. Meaning that there is not necessarily an obvious right or a patently wrong solution. And the solutions are not necessarily permanent. What works today does not necessarily work tomorrow. So solutions change over time, and what is a solution today could become a problem tomorrow.

Addressing these combined issues of complexity and of wickedness is going to require a particular kind of intervention, a particular kind of solution. We are now realising that food security – much like the issue of climate change – is what’s known as a collective-action problem, a problem that involves multiple stakeholders, and will require collective action from all of these stakeholders. One example that is foremost in our minds, for instance, is how we manage the current drought in the Western Cape; if individuals don’t manage their water consumption, then all in the Western Cape are all going to suffer.

We will have to think of new ways of doing business. For instance, if we continue to accept the promotion the consumption of unhealthy foods and beverages – foods whose consumption will lead to problems of overweight, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease – that will have longtermconsequences for the economy as a whole. This is likely to mean that we will all have to pay more for the National Health Insurance System when it is introduced as there will be more people who are living with nutrition-related non-communicable diseases.

Consequently even though the different stakeholders in the food system may not all agree on the causes of the problem or even the nature of the solution, finding a way forward will demand collective action. It will require partnering, often with groups that may find it difficult to form such partnerships. While we may not all be happy or benefit from the solution – one person or business may benefit or lose more than the other – we will have to understand that if we don’t deal with food insecurity, the consequences will be negative for all South Africans.

related Articles

CoE-FS 10th Anniversary Symposium – Opening session

Date: Wednesday, 22 May 2024 Time: 09h00 – 10h00 (SAST) Co-chaired by Professor Julian May (CoE-FS Director) and Professor Lise…

CoE-FS 10th Anniversary Symposium – Governance and policy

Date: Wednesday, 22 May 2024 Time: 10h00 – 12h00 (SAST) Register for Zoom here. Co-chaired by Professor Julian May (CoE-FS…

CoE-FS grantees, researchers take part in the 2024 Montpellier Process

The CoE-FS grantees were joined by students from Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Kenya, the Netherlands, Senegal, Spain, the UK, and…