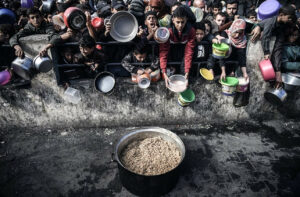

The Israeli regime’s cutting off and restriction of food and water in its war on Gaza has a hauntingly long history and the implications will be felt for generations to come. Photo @ultrapalestine / Instagram.

Multiple accusations of violations of international humanitarian law have been levied against the Israeli government over the last three months, including collective punishment; the execution of surrendered Palestinians; the mass murder and detainment of children; the murder of at least 110 journalists and over 320 healthcare workers; attacks on refugee camps, hospitals, schools, universities and places of worship; and the use of white phosphorous in areas with high population densities. Now, the use of starvation as a weapon of war must be added to this list. These charges will be heard by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at The Hague on 11 and 12 January 2024.

On 29 December 2023, South Africa lodged an Application with the ICJ that accuses the State of Israel of breaching the 1948 Genocide Convention, inter alia by “the starvation of civilians as a method of warfare” (paragraph 2) and “failure to provide or ensure essential food … for the besieged and blockaded Palestinian people, which has pushed them to the brink of famine” (paragraph 4). Genocide refers to acts committed in order “to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group”, including “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part”.

In the context of the deliberately created ongoing food crisis in Gaza, the Application mentions “food” 79 times, “hunger” 30 times, “starvation” 20 times, and “famine” five times. Specific acts of genocide identified in the Application include “causing widespread hunger, dehydration and starvation to besieged Palestinians in Gaza” (paragraph 114(4)). Further, the Convention provides that “direct and public incitement to commit genocide” is a crime in its own right.

Less than three months earlier, on 7 October 2023, Palestinian armed groups launched an attack, targeting Israeli military installations and capturing military and civilian hostages, with a reported civilian death toll of 695 Israelis and 71 foreigners. In response, Israeli defence minister Yoav Gallant announced a complete and shockingly disproportionate siege on Gaza, cutting off essential supplies such as food, water, electricity and cooking gas.

Due to Israel’s refusal to allow adequate humanitarian supplies into Gaza, only about 10% of the food the besieged residents need has been trucked in, according to the United Nations (UN). By mid-November, the World Food Programme (WFP) was already warning that “people are facing the immediate possibility of starvation”. By 10 December, WFP announced that “half of Gaza’s population” (1.2 million people) were starving.

As noted by Tufts University’s Tom Dannenbaum, this is “an abnormally clear-cut instance of starving civilians as a means of war, an unambiguous violation of human rights”.

This is compounded by tactics that target Gaza’s water supply, as safe water is a critical component of nutrition security. Despite Israel’s claim that it had resumed water supply to Gaza on 15 October, multiple sources report a polluted or only intermittent supply. Chemicals emanating from weapons used will or have already entered the water supply, and, more recently, Israel stated its plans to pump seawater into underground tunnels, which would have dire consequences for the already crumbling water infrastructure.

Starvation is one of the most barbaric strategies used to wage war. It is wielded to kill slowly, to crush emotionally, and ultimately to obliterate. Limiting a people’s access to food and water, and allowing them to teeter on the brink of starvation and famine, ensures dire and irreversible consequences that will endure for generations to come.

A haunting history

Before this latest siege, 80% of the population of Gaza already relied on humanitarian aid as their main source of food and nutrition. Now, as bakeries, community kitchens and food markets are bombed, taps run dry, crops are destroyed, and access to international food aid is denied, we are haunted by memories of hunger being used as a weapon of war.

More than 2 000 years ago, Sun Tzu wrote in The Art of War of the interconnectedness of war and food. Julius Caesar is believed to have used starvation as a weapon of war. In South Africa, Shaka used “scorched earth” tactics in his military campaigns, as did the British during the South African War.

During World War II, Nazi Germany carried out ‘Der Hungerplan’. By blockading cities such as Leningrad, inhabitants were subjected to prolonged starvation, resulting in the deaths of at least one million civilians. In the Jewish ghettoes in Poland, the Nazis controlled and rationed access to food at below-subsistence levels. The Nazi governor in occupied Poland wrote, “that we sentence 1.2 million Jews to die of hunger should be noted only marginally”.

By blockading cities such as Leningrad, the Nazi regime subjected inhabitants to prolonged starvation, resulting in the deaths of at least one million civilians. Photo RIA Novosti archive / Commons Wikimedia.

Also in World War II, German occupying forces blockaded part of the Netherlands for several months in 1944, prohibiting all movements of food and directly causing thousands of deaths by starvation during the Dutch Hunger Winter.

While the famine in Ethiopia in the 1980s was triggered by drought and harvest failure, it took place during a civil war during which trade was restricted, markets in Tigray were bombed, and humanitarian access to affected areas was denied. More than half a million people died.

A 2021 report titled “Starvation Makers: The use of starvation by warring parties in Yemen” documents systematic violations of the right to food since the war began in 2015, including airstrikes that targeted farms and irrigation infrastructure, fishing boats and water facilities, as well as restrictions on humanitarian relief that denied access to food and water to starving civilians. Disruptions to food systems and health services have had devastating impacts on food and nutrition security. By 2020, the UN estimated that 131 000 out of 233 000 deaths during the ongoing war in Yemen were due to “indirect causes such as lack of food”.

Food crimes in Palestine

Since the Israeli occupation began in 1948, the Palestinian food system has been under assault. In addition to restrictions on marking and mobility, the destruction of crops has been a frequently used and widely criticised method of warfare by the Israeli government.

Olive groves, central to Palestinian livelihoods and culture, have been destroyed by Israeli forces, both in times of conflict and in relative peace. In parts of Gaza such as Khan Younis, farmers require passes to enter and tend to their land.

Imports and exports are also strictly controlled by the Israeli regime, through the enforcement of a list of banned or restricted items, including dried fruits, coriander, jam and chocolate. Agricultural essentials such as fertilisers are hard to come by, having been deemed as a potential ingredient for bombmaking.

By 10 December, the World Food Programme announced that “half of Gaza’s population” (1.2 million people) were starving. Photo @ultrapalestine / Instagram.

In 2019, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs noted that the expansion of Gaza’s fishing limits by Israel was a positive development, but remained well below the nautical miles that were agreed at the 1993 Oslo Accords, which was therefore violated. As recently as August 2023, the fishing community in Gaza staged a sit-in to protest the ongoing arrests of fisherfolk, seizure of boats and, being “constantly chased, harassed, intimidated and even killed by Israeli forces”. Less than a month later, Israel closed Kerem Shalom, the main commercial crossing in Gaza, a further blow to fisherfolk and an already ailing economy.

The current conflict continues this pattern: during the harvest season in October and November 2023, many Palestinian farmers could not tend to their farms and livestock. Constant bombardment displaced farming families, cutting off their financial lifeline and main source of food. According to reports in early November, nearly 20 Palestinian farmers near Khan Younis had been killed.

Slow, long-lasting violence

In 2003, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food found a “terrible situation of malnutrition” in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, and concluded that, “although the Government of Israel, as the Occupying Power in the Territories, has the legal obligation under international law to ensure the right to food of the civilian Palestinian population, it is failing to meet this responsibility”. Three years later, Dov Weisglass, an adviser to then Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, declared that, “the idea is to put the Palestinians on a diet, but not to make them die of hunger”.

Throughout the 75-year occupation, international bodies and human rights watchdogs, among others including the Israeli press, have voiced concern about the Israeli regime’s use of hunger as a weapon. In 2018, the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) reported an urgent need for strategic action to address child and maternal malnutrition in Gaza.

Already, in 2018, the United Nations Children’s Fund reported an urgent need for strategic action to address child and maternal malnutrition in Gaza. Photo @ultrapalestine / Instagram.

The urgency of this strategic action is grounded in the widely documented, irreversible impact of malnourishment on a child’s health and development. Children younger than five years of age, and unborn children, are particularly at risk, and the nutritional shock of the current hunger in Gaza can permanently constrain their physical and cognitive development. The low birth weights that are likely to result from maternal malnutrition will also increase the risk of infant mortality or disability. Polluted water supplies, the collapse of solid waste removal systems, and poor sanitation increase the risk of child diarrhoea, further heightening the risk of chronic malnutrition.

The implications of weaponising starvation extend beyond immediate suffering and long-term malnutrition. Where there is not immediate death and destruction by bombs and bullets, the deliberate use of hunger as a weapon of war is etched into the fabric of affected communities, resulting in a lifetime of trauma and undermining the prospects for peace and reconciliation, possibly for generations.

Call to action

One of the most concerning aspects of Israel’s indiscriminate bombing of the people of Gaza is the role of Israel’s allies, especially the United States, in endorsing and enabling this attack. The inability of the UN Security Council (UNSC) to uphold its humanitarian mandate was thrown into sharp focus when the US used its veto to prevent condemnation of Israel and protect civilian lives in Gaza, by calling for a ceasefire. Citizens across the world should demand an overhaul of the UNSC and its outdated and paralysing voting rules.

The right to adequate food is protected by the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which has been signed and ratified by 171 countries, including Israel. The intentional starvation of civilians is listed as a war crime in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. The Israeli government should be investigated for war crimes in Gaza, and perpetrators should be prosecuted, as should those who have advocated the use of starvation. The South African government’s application to the ICJ, currently supported only by Turkey, Jordan, Malaysia, and Bolivia should be supported by other governments and by international agencies that are concerned with human rights, especially the rights of children to adequate nutrition.

If the permanent effects of chronic malnutrition are to be avoided, humanitarian assistance for Gaza is required at a large scale, immediately and without interference by the Israeli regime. The low levels of child malnutrition following the siege of Sarajevo in the early 1990s were a result of favourable food security conditions prior to the conflict, and the huge international response in terms of food aid. The first does not apply in Gaza, and the second is not yet forthcoming, making the need for food aid to Gaza all the more urgent.

Finally, a stronger response is needed from the university sector. Whatever our nationality, ethnicity, religion or politics, academics and academic institutions should unite to condemn violations of international law, wherever they occur and whoever perpetrates them. Rarely has the cliché been more apposite: This is not about politics; it is about our common humanity.

Professor Stephen Devereux: Stephen Devereux is a development economist working on food security, famine, rural livelihoods, social protection and poverty reduction issues. His research experience has been mainly in eastern and southern Africa. He works at the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex, UK, where he is Co-Director of the Centre for Social Protection. He holds the NRF Research Chair in Social Protection for Food Security, affiliated to the DSI–NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security and the Institute for Social Development at the University of the Western Cape, South Africa. He writes in his personal capacity.

Professor Julian May: Julian May is the Director of the DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security (CoE-FS), which is hosted by the University of the Western Cape and co-hosted by the University of Pretoria. He holds the UNESCO Chair in Science and Education for African Food Systems. He has worked on options for poverty reduction including land reform, social grants, information technology and urban agriculture in Africa and in the Indian Ocean Islands. He has also worked on the development and use of systems for monitoring the impact of policy using official statistics, impact assessment and action research. His current research focuses on food security, childhood deprivation and malnutrition. He currently serves on the National Planning Commission and the Council of the Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf). He writes in his personal capacity.

Carla Bernardo: Carla Bernardo is the Communication and Engagement Manager at the DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security (CoE-FS), which is hosted by the University of the Western Cape and co-hosted by the University of Pretoria. She is the project lead of the Infant and Young Child Feeding Advocacy Project housed within the CoE-FS, and is completing her Master’s in Political Communication at the University of Cape Town. She writes in her personal capacity.

related Articles

How to use the law against the law, for better systems

At the recent Food Indaba “Hunger and Power” conference, activists, analysts and academics explored ways in which to use the…

Hunger as a weapon: in war and at home

Displaced women making bread during the humanitarian pause in Khan Younis. UNRWA photo by Ashraf Amra. From Gaza and Ethiopia,…

The normalisation of hunger in South Africa

A message from residents in Touwsrivier to local government. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks/CoE-FS. This article was originally published by the Institute…